Five Invisible Characters That Still Matter in Word Processing and Layout

In earlier eras of word processing, users were much more likely to encounter explanations of document structure—not because everyone had to become an expert, but because knowledge was shared differently. Software shipped with detailed manuals, user groups and training classes focused on how documents worked under the hood, and power users routinely shared mental models and tips. (Who remembers being turned onto WordPerfect’s Reveal Codes?) Today’s writing tools are simpler to use and much better at hiding complexity, but that also means fewer opportunities for users to learn that invisible characters even exist, much less that they have different attributes and consequences.

We’ll look at five invisible characters that shape how text behaves: the regular space, non-breaking space, tab, hard return, and soft return. You already use regular spaces and hard returns, but understanding the other three—and when to employ them—can help you create cleaner, more professional documents and troubleshoot layout problems.

How to See Invisible Characters

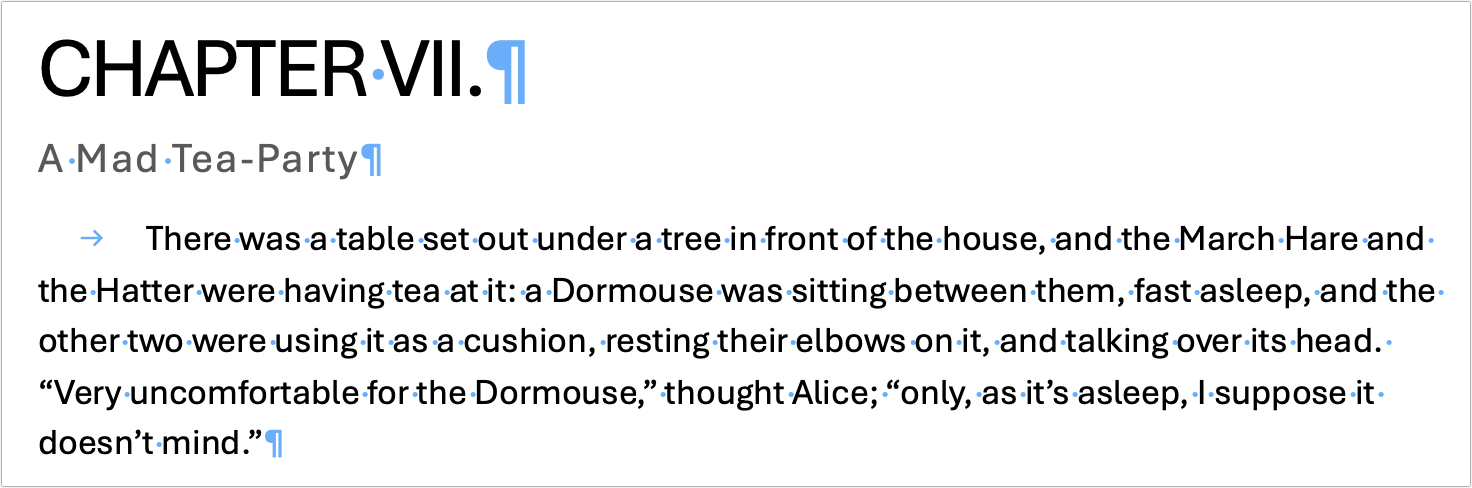

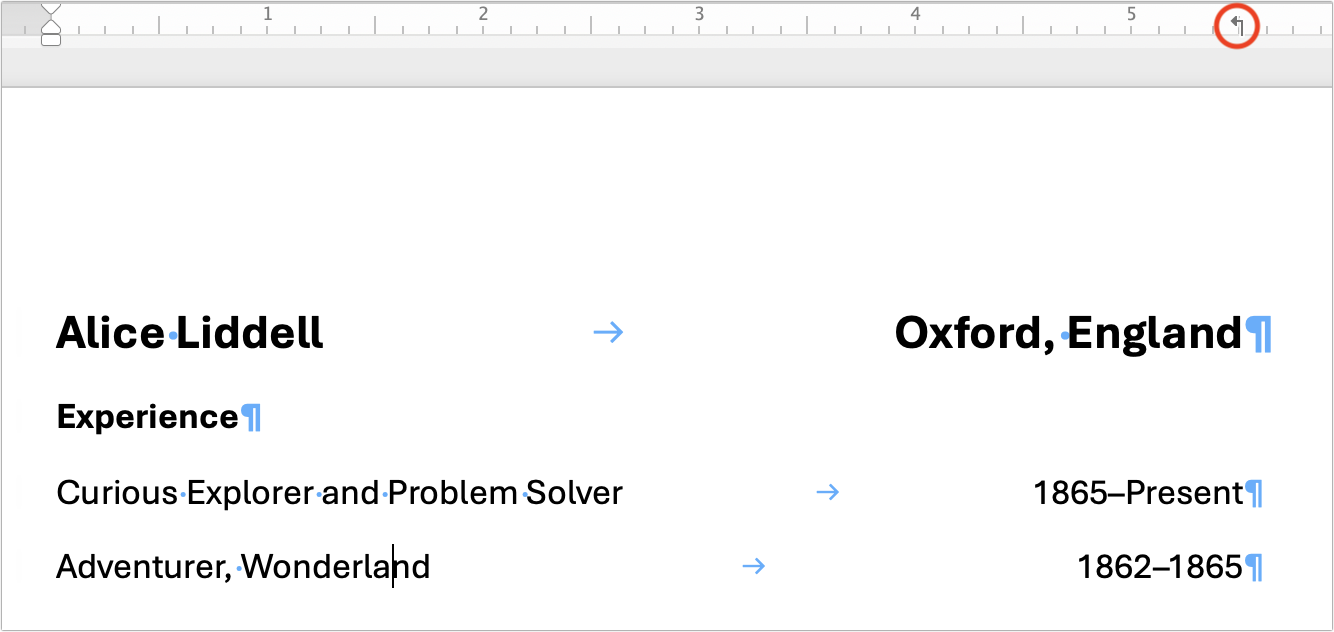

Nearly every text editor, word processor, and page layout app includes an option to show “invisibles” (the term may vary, but the concept is the same). When Show Invisibles is enabled, you’ll see dots, arrows, paragraph marks, and other symbols that represent normally invisible characters. They typically appear in a color different from the default text color, such as the blue characters in the screenshot below.

Regular Spaces Versus Non-Breaking Spaces

Everyone knows what a space is—it’s a breakable separator between words. By “breakable,” we mean the next word can wrap down to the next line of text. A regular space expresses the default intent: separate words and allow normal line wrapping.

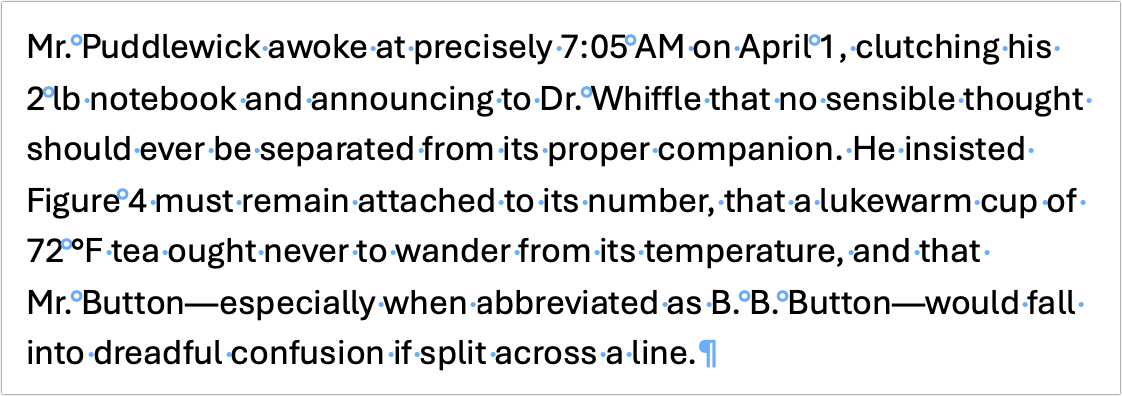

However, there are situations when you want two words to stay together because it could be confusing if the second one wraps down to the next line. In those situations, you can use a non-breaking space—inserted by pressing Option-Space on the Mac or (usually) Control-Shift-Space in Windows, and represented in HTML by . Word processors usually distinguish non-breaking spaces from regular spaces when showing invisibles—for example, Microsoft Word uses a small open circle for non-breaking spaces and a dot for regular spaces.

When would you use non-breaking spaces?

● Numbers with units: The most common use of non-breaking spaces is to keep numbers with their units, such as “1 TB” or “72 ºF.”

● Names with titles, and initials with surnames: Non-breaking spaces are also useful for names with titles, such as “Mr. Spock,” and for people who go by their initials, such as “J. K. Rowling.”

● Short phrases that function as a single unit: Some short phrases are conceptually one piece and should not be split across lines. This includes dates (“January 19”), times (“9:41 AM”), version numbers (“iOS 26”), and textual references (“Figure 4”).

If you are using page layout software, check whether it has character styling that keeps words together, such as Adobe InDesign’s No Break style.

Tabs Versus Spaces

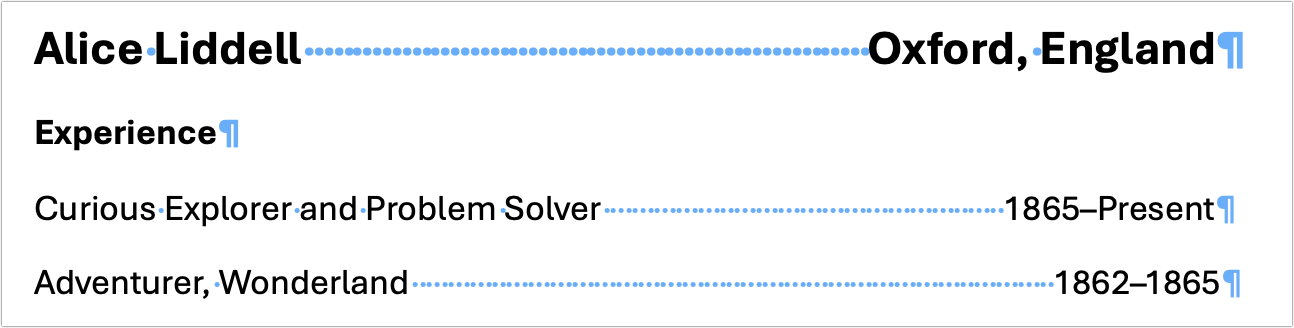

Because spaces separate words, many people overuse them to increase visual separation between words and to align text, such as in a résumé with a job title on the left and the associated dates on the right.

Unfortunately, spaces work poorly for aligning text because most fonts are proportional, meaning a lowercase i is thinner than an uppercase W. Therefore, spaces can’t align text perfectly—not because spaces differ in width, but because the characters before them do. Ragged alignment in a printed document is easily noticeable and looks unprofessional.

The simple solution is to use a tab, which aligns to a fixed position marked by a tab stop. Pressing the Tab key inserts a tab to the next tab stop, which can usually align text to the left, right (shown below), center, or decimal point. Most apps have a few default tab stops, and you may never need anything different. However, you can usually customize the behavior and location of the tab stops. First, put your insertion point in the paragraph you want to work in, or select a swath of paragraphs. Then, either use the ruler to customize the stops or use dedicated tab controls, such as in Microsoft Word’s Format > Paragraph > Tabs dialog. More advanced users will want to customize tab stops within paragraph styles.

Although we can now use tables and layout tools for much of what tabs were necessary for in the early days of word processing, tabs remain useful in some situations, such as:

● Horizontal placement: If you want your signature to appear below a letter on the right, you could right-align the entire line, but a right-aligned tab stop gives you more control over where the signature appears.

● Simple lists: For a short contact list that includes name, phone, and email, setting a few tab stops could be easier than inserting and formatting a table.

● Quick outlines: When creating a quick outline, such as an agenda with left-aligned times and indented session titles, use tabs to create indentation. This preserves the outline structure and makes it easier to adjust later.

If you’re trying to align text rather than separate words, a tab expresses that intent far better than spaces ever can.

Hard Returns Versus Soft Returns

Most people understand hard returns, which separate one paragraph from the next. Pressing Return (Mac) or Enter (Windows) creates a hard return. For example, you’d put a return between a heading paragraph and the following body paragraph. Less well-known are soft returns, which start a new line within a paragraph, but do not end the paragraph. An important side effect of a soft return is that whatever paragraph formatting is applied to the paragraph will continue to apply to the new line. To type a soft return, type Shift-Return or Shift-Enter. (In HTML, paragraphs are marked with a pair of <p></p> tags, while soft returns use the <br> tag.)

The most common reasons to use soft returns include:

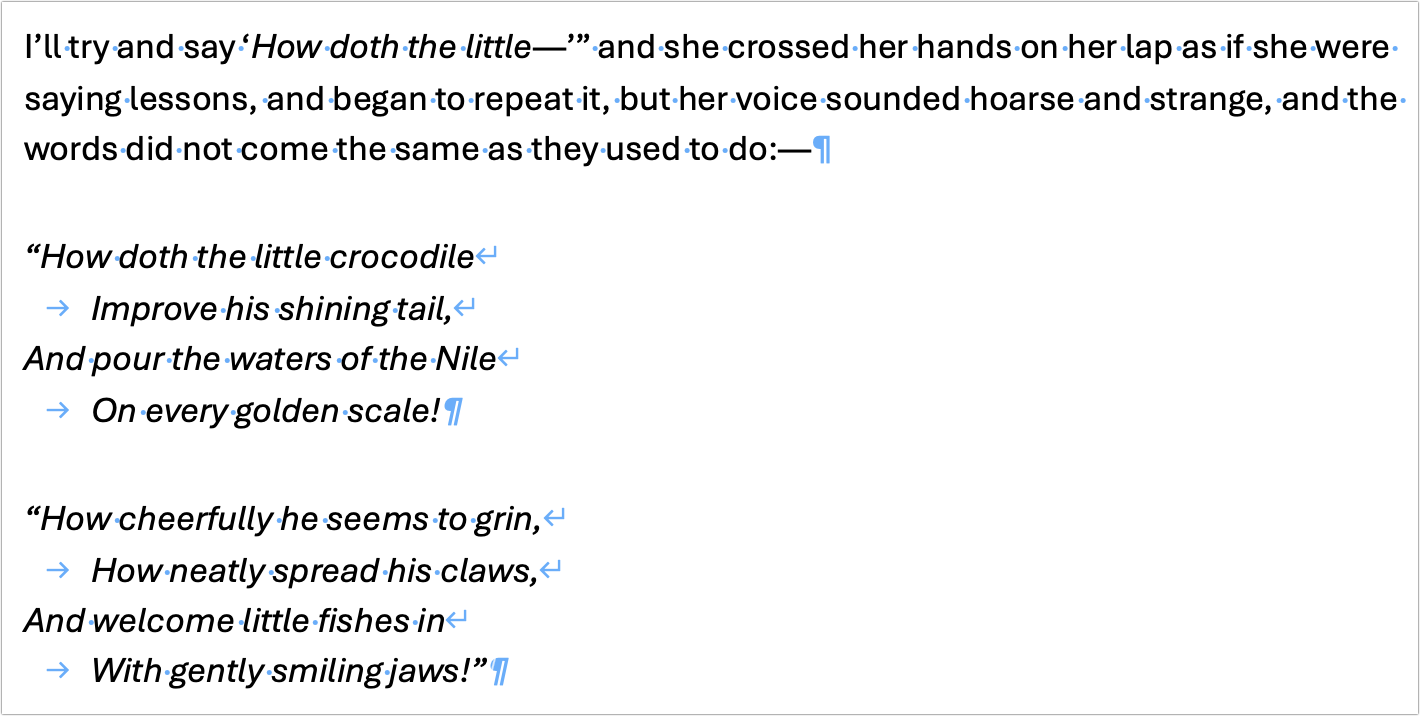

● Multi-line formatting: Some blocks of text are conceptually single paragraphs displayed across multiple lines. Think of postal addresses, poetry, and song lyrics.

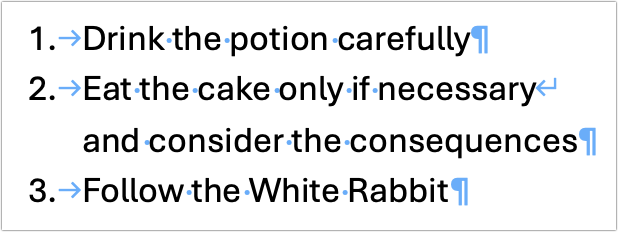

● Maintain numbering or outline level: In lists and outlines, hard returns increment a list number or add a new outline entry, whereas soft returns insert a line break without creating a new number or outline entry. (HTML uses <li></li> tags to denote list items, but you can still use <br> tags within list items.)

● Narrow layouts: Soft returns are often necessary to force text down to the next line in columns, sidebars, captions, and callouts. They are a helpful supplement to non-breaking spaces.

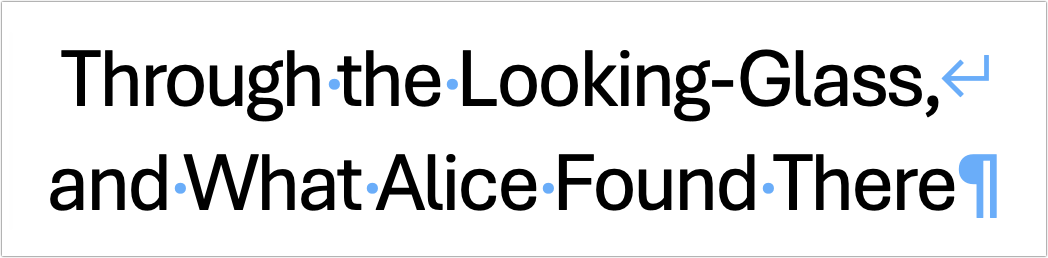

● Intentional formatting: In multi-line headings, captions, and labels, aim to keep lines roughly equal in length, with the last line slightly longer than the others. Use soft returns to adjust line lengths as needed.

In short, use hard returns to separate paragraphs that are standalone units of text. Use soft returns to add line breaks within a chunk of text that is conceptually a single paragraph.

When Invisible Characters Cause Problems

Understanding non-breaking spaces, tabs, and soft returns is important because they can appear in your text without you noticing. Someone might have intentionally added them, or you might have accidentally included them by copying and pasting from PDFs or the Web. Some common invisible character issues you might encounter while formatting include:

● Short lines: If a line appears unusually short, it could be caused by a soft return moving text to the next line or a non-breaking space causing two words to wrap down together.

● Fragile alignment: If aligned text shifts when you change fonts or alignment, it’s usually because spaces are being used instead of tabs.

● Text gaps: If there’s unexpected white space between words, check if a tab is there instead of a space.

● Broken list numbering: In an automatically numbered list, broken numbering may be explained by a soft return being used instead of a hard return. Fix it by deleting the return between the misnumbered line and the one above, pressing Return to insert a new hard return, and repeating as needed.

Remember, you don’t have to type with invisible characters showing, but if your text has mysterious white space or odd line wrapping, you can likely resolve those problems quickly by viewing invisible characters and making sure they are doing what they should.